Many components combine to make the sport of horse racing so popular all around the world. The sight of the finest equine athletes on the planet in full flow is chief amongst them, with the stars of the sport providing moments of magic and enduring drama year after year. One thing that is absolutely key to racing’s existence though, and possibly more so than in any other sport, is the betting activity that surrounds it.

Many components combine to make the sport of horse racing so popular all around the world. The sight of the finest equine athletes on the planet in full flow is chief amongst them, with the stars of the sport providing moments of magic and enduring drama year after year. One thing that is absolutely key to racing’s existence though, and possibly more so than in any other sport, is the betting activity that surrounds it.

Horse racing and betting are simply made for each other and continue to enjoy a thriving partnership centuries after they first joined forces. The horses and jockeys may be the stars, but for many, it is the punting element that really makes the sport tick. And just as with the sporting side of things, the betting market also features its own peculiar jargon and terminology – with which the uninitiated may be unfamiliar but which is really pretty straightforward once you get the hang of it.

And it is to two of the more frequently used betting terms to which we turn here: the steamer and the drifter. We will be looking both at the definitions of the terms and how they fit into the overall betting picture.

The Betting Market

In order to get to grips with this terminology, we first need to be aware of how the betting market operates. And specifically the fact that, far from being set in stone, the initial odds provided by the compilers are in a state of flux almost from the moment they are made live to the betting public. And what makes these odds move? None other than the driving force of the betting world: money!

With the aim of the bookmaker being to come out on top no matter what the outcome of a particular race, it follows that the layers should aspire to attract business for each of the runners in the field. However, this doesn’t always happen, and in the face of an uneven spread of stakes, the bookmakers will react by adjusting the prices; shortening the odds of the well-backed runners in an effort to deter future bets, and lengthening the odds of the less supported runners in order to attract investment.

And much of the time, this constant price tweaking has the desired effect, with a significant percentage of runners continuing to hover around their initial price right up until the moment at which the race begins – perhaps lengthening a little, or shortening slightly. There are however those horses whose price continues to move in a particular direction, forcing the bookmakers to shorten or lengthen the price over and over again. And it is these runners who have come to be known as the steamers and drifters of the racing world.

What Is A Steamer?

In relation to the above, a steamer is simply a horse that is very well backed in the market and continues to be well supported even as the bookmaker continues to shorten the price. For example, a runner being backed at an initial price of 12/1 and continuing to be punted at all prices down to 6/1 or perhaps even shorter.

The exact origins of the term “steamer” appear to have been a little lost in betting history, but it seems most likely to be related to the fact that the odds appear to be steaming in – in the manner of a steam train arriving at the station, or a steamboat powering to shore, possibly overloaded with excitable punters honking the horn.

Why Does A Horse Steam?

So that’s what a steamer is. But why do they come about? What causes the betting public to latch on to these runners in such a manner, moving their odds so far away from the professional odds compilers’ initial assessment. In truth, there can be several reasons, but the following are amongst the most common:

- Psychological Factors: Also known as the bandwagon effect. This all comes down to the way in which punters react when seeing the price of a horse shorten. The thought process of some going along the lines of: why is the horse shortening? Someone must know something I don’t. I had better back it myself, don’t want to miss out after all. This of course leads to further money being staked on the horse, forcing the bookmakers to shorten the price even more, and so on.

- The Weather: Whatever you might make of the bandwagon effect, it’s hard to argue with the rationale behind this next influence. The fact is that some horses simply have a marked preference when it comes to the going, and as such a change in ground conditions can dramatically affect their chances of winning a given race. A soft ground specialist may be a 20/1 outsider on the morning of the race if the ground is described as good but should the heavens open, you can expect to see the odds of such a runner shorten significantly.

- Trainer/Jockey Form: Punters rarely need too much encouragement to follow a yard or rider who seems to be going well. Should you see a trainer/jockey have a couple of winners in the early races on a card, don’t be surprised to see their later entries shorten in price. The bigger the name of the trainer or jockey in question, the bigger the effect is likely to be.

- Tipsters: There are many tipsters out there, some with a better record and bigger following than others. Whilst the selections from the local village rag may have minimal impact on the betting market, those made by the flagship pundit in the national industry paper can often make a significant splash, as his/her followers rush to back the latest hot tip.

- Trainer Comments: If anyone should have a good idea of how a horse is about to perform, it is surely the individual responsible for readying them for their day at the races. No surprise then that the betting public can latch on to positive trainer comments, and often to the extent that a steamer is created.

What Is A Drifter?

Drifters are the runners at the opposite end of the spectrum to the steamer. The term refers to those horses who attract very little support at their opening price and continue to be ignored by punters even as they are made available at longer and longer prices, for example, a horse opening up at 10/1 and being pushed out to 12/1, then 14/1, 16/1 and so on.

Going back to our boating analogy, the drifter is the steamboat with the engines switched off which, rather than powering along in the direction of the shoreline, is merely allowed to drift further and further out to sea, with the punters paying it very little attention at all.

Why Does A Horse Drift?

So what is it that results in a runner being so unloved by the betting public? Again, there can be several factors that contribute to a drift, many of which are closely related to those which cause a runner to steam.

- Psychological Factors: Whilst generally not so strong as in the creation of steamers, a sort of reverse bandwagon effect can increase the extent to which a horse drifts. A punter may well initially fancy a runner, only to be deterred from placing a bet due to the horse moving out in the betting, with again similar questions running through the bettors mind: why is this horse drifting? Does somebody know something I don’t? Is the horse not fully fit? and so on.

- The Weather: Just as conditions can alter in favour of certain runners, they can just as easily turn against others. For every soft ground horse who shortens in the betting when the rain arrives, there is another quick ground specialist who will begin to drift almost as soon as the rain starts to fall.

- Negative Trainer Comments: Should a trainer utter anything along the lines of a horse not being 100% fit, not having this race as their primary target, or being likely to improve for the run, don’t be surprised to see the horse “take a walk in the market”.

- Paddock Problems: One of the primary causes of a late drift can come as a result of a horse’s pre-race appearance. Is the runner sweating profusely in the paddock when usually calm and relaxed? Or are they looking particularly hard to handle on the way down to the start? Both may be seen as negative by the betting public and result in the odds on the horse in question lengthening.

- The Effect Of Steamers: It is also important to remember that on occasion the odds on a runner may lengthen, not due to anything particularly negative aspect about their chances, but rather to counterbalance other runners in the field being shortened in price. The shortening of one runner must necessarily lead to the lengthening of another if the bookmaker is to maintain a competitive book.

What Is the Significance of A Steamer or Drifter?

The answer to this question largely depends on two factors. Firstly, how close are we to the start time of the race? And secondly, how big is the race? The key point in each instance is just how much money it takes to move a price.

The odds for the majority of events are made live on the evening before the race – and at that opening point the total amount staked on the race is, of course, zero. Whilst it doesn’t take long for the first bets to placed, the initial flow of stakes will often be little more than a trickle, beginning to increase on the morning of the race and continuing to climb further right up until the off time.

As such, a £100 single placed the night before the race could be a fairly significant bet in relation to the total amount staked – and it could be possibly enough to result in a price change. If placed 10 minutes before the off, however, that same bet is likely to be a mere drop in the ocean and would be unlikely to affect the odds at all. The general rule to note here is, the closer we are to the off time, the more money it takes to move a price and the more significance can be placed upon a steamer or drifter.

And related to the above, it is considerably easier to move a price in a small race than in a major contest. A £1,000 win single in the first race at Southwell on a Tuesday afternoon for example is likely to send at least a ripple through what is likely to be a relatively weak market. Whereas in a huge public race such as the Grand National, the same stake would barely have any impact at all. The bigger the race, the more money is required to create a steamer or drifter and hence the more significant the steam or drift is.

Is It Better To Steam or Drift?

Common sense dictates that a steamer should be taken as positive and a drifter as a negative – at least in terms of the chances of winning the race. A runner shortening from 5/1 into 4/1 for example has moved from a perceived chance of winning of 16.67% to one of 20%, whereas a runner moving from 5/1 to 6/1 has shifted from a 16.67% perceived chance to one of 14.28%.

Remembering that the odds are at their most accurate at the moment at which the race goes off, it is clearly more desirable to see your runner shorten in price as that off time approaches than it is to see the odds on your selection lengthen.

But Which Is Better?

An increased chance of winning the race is all well and good, but in and of itself does not make a steamer a better bet than a drifter. And the reason for this is that when determining the best betting option, it is not the win percentage that matters but rather the long-term success rate.

Take for example a backer who achieved a 50% strike rate with his selections – an admirable figure, but not much good if every horse he backs is priced at below even money. Now consider another punter who manages a strike rate of only 10% – not so good on the face of it, but easily enough to secure a long-term net win should all of his bets be placed at odds of 12/1 or higher. Bearing that in mind a move towards a shorter price does not automatically represent a better bet and a drift to a bigger price does not necessarily signify a worse bet.

What matters is how closely the odds correspond to the actual winning chances of the horse. The exact chance of a runner winning any given race is all but impossible to determine with 100% accuracy in advance, but we can study the win percentages returned by runners within certain odds ranges after the event. Do runners priced at evens win roughly half the time on average for example? 10/1 shots win one time out of 11? And so on.

Favourite Longshot Bias

Helpfully, the aforementioned study has been undertaken on numerous occasions in the past, and time and again it returns very similar results.

In an unbiased market, there should be no benefit derived from blindly backing all runners at a certain price overall runners at another i.e. the long-term returns generated by a £1 single on every 100/1 shot should be the same as those resulting from a £1 single on every 5/4 shot. The 100/1 shots will of course win far less frequently, but this will be levelled out by the much greater returns when they do win. However, when looking at the returns generated across the range of prices in horse racing, this is not what we find.

What the results instead show is a significant bias in favour of the shorter priced runners, a phenomenon which has come to be known as the favourite/longshot bias. The table below, which shows the returns generated from backing all runners across a range of prices during the 1989 season serves as a good illustration of this bias in action.

| Odds Range | Wins | Runs | % Return |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/5 to 1/2 | 249 | 344 | 100.52 |

| 4/7 to 5/4 | 881 | 1780 | 95.35 |

| 6/4 to 3/1 | 2187 | 7774 | 91.91 |

| 7/2 to 6/1 | 3464 | 21681 | 89.68 |

| 8/1 to 20/1 | 2566 | 53741 | 63.11 |

| 25/1 to 100/1 | 441 | 43426 | 32.24 |

What this table effectively shows is that shorter prices generate better returns in the long run. With the returns becoming steadily worse as we move down the price bands. In terms of steamers and drifters, this table would suggest that runners shortening in price (steamers) are moving in the right direction both in terms of their chance of winning and the long term returns, with the opposite being true of those runners going out in price (drifters). Of course, this is an overall picture, and cases should be assessed on their individual merits; but in general, we would suggest it is much better to be on a steamer than a drifter.

All aboard the Steam Train?

With the evidence suggesting that it is preferable to be on a steamer as opposed to a drifter, the next question on many punters lips will be, “is it possible to get a net win simply by backing every steamer?”.

Helpfully, this has also been looked at in the past, and the results did indeed show a window of opportunity for punters. Looking at the period between 2014 and 2017, backing all 1072 horses who shortened by six points or more would have yielded a 13.43% strike rate and +15.26% return on investment. There is however just one small problem. The results of this study – and many others like it – were calculated using the peak price of the horse, i.e. the odds on offer before the horse began to steam. And this leads us to the main issue with any steamer related betting strategy. How exactly do we know when a horse is about to steam?

And the answer is, we simply can’t know for sure. Many horses shorten in price only to then drift back out again, whilst others do the reverse. Attempting to weed out the genuine steamers and drifters from all of this betting noise is no easy task but that doesn’t stop people from trying. And if we can spot the patterns early, the results may well be rewarding.

Beating The SP: The Betting Approach

The obvious benefit to spotting a steamer early – be that by reacting quickly to ground changes, identifying a yard in form, or otherwise – is that by placing a bet on a horse which subsequently shortens, we will be on at a price that is often significantly greater than that available at the off; this is a strategy destined to pay off in the long run.

Lucrative as it may be, this straight backing strategy does not avoid the issue of variance – for some simply part of the betting rollercoaster, but for others an unnecessary excitement to be avoided at all costs. All is not lost however for the more risk-averse punter, as there is a way in which to come out on top from a steamer, or indeed a drifter, which – if successfully employed – eliminates the element of risk entirely.

Securing a Net Win: Trading

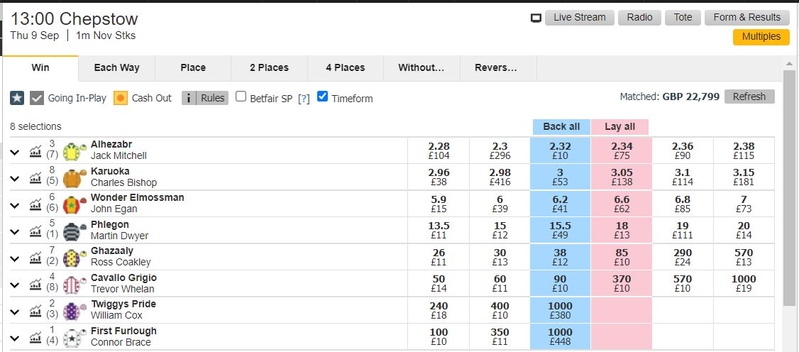

Assuming that, for whatever reason, we can be confident that the odds on a runner will change between now and the race beginning, how can we use this information to secure a net win, no matter what the outcome of the race? The answer lies in the ability to trade, something that is provided by the betting exchanges.

Trading A Steamer: Back To Lay

If we are fairly certain that a runner is going to shorten in price, then the approach to take is to back the selection to win now, with the aim of then laying the runner at a shorter price later. For example, consider a scenario where we place a £10 win bet at odds of 6/1 and (as anticipated) the price subsequently shortens to, say, 4/1. We will now be in a position to either give ourselves a free bet by laying the runner for £10 at odds of 4/1, or to secure a small net win no matter what the result. In this instance, a £4 net win (less any commission taken by the exchange) could be secured by laying the 4/1 price for a stake of £14.

- Should the horse win, you would receive £60 in winnings from your £10 win bet at 6/1 and only have to pay out £56 as a result of the £14 lay bet at 4/1 – equalling a £4 net win overall.

- And should the selection lose, you would of course lose your £10 stake on the 6/1 win bet, but win the £14 lay portion of the bet – again equalling a net win of £4 overall.

Trading A Drifter: Lay To Back

But what about the scenario where we suspect a runner will drift to a bigger price than that which is currently available? Can we secure a net win under these circumstances? Yes we can, and the way in which do so is simply by employing the method outlined above in reverse, i.e. laying the selection at the current odds, and then backing the runner once it has drifted to a bigger price.

For example, say we lay a runner for £10 at 5/1, and then see the price drift out to 11/1. If we then place a £10 win bet on the selection, we will have effectively given ourselves a free shot at £60 should the horse win the race – losing £50 on the lay bet, but winning £110 from the win bet. Or, just as with the Back to Lay example, we may wish to secure ourselves an equal net win either way. In this instance, a £5 net win could be secured by reducing the stake of the win bet placed at 11/1 from £10 to £5.

- Should the horse win, you would lose £50 from your £10 lay bet at 5/1, but win £55 as a result of your £5 win bet at 11/1– equalling a £5 net win overall.

- And should the selection lose, you would of course lose your £5 stake on the 11/1 win bet, but win £10 from the lay portion of the bet – again equalling a net win of £5 overall.

As with many things in the betting world, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to steamers and drifters. Some horses will steam off the boards and lose, whilst others will drift alarmingly only to romp home in front. That said, it never hurts to be aware of emerging patterns in the betting market and what may potentially be causing them. Some odds movements may well represent a lucrative opportunity to steam into, whilst others may be best left to drift on by.