Football, by which we mean association football, or soccer, is the world’s most popular sport. Its biggest stars and best players are known around the world and can earn astronomical sums, with a 2023 report in Forbes showing that the three highest-paid athletes in that year were all exponents of the beautiful game.

Football, by which we mean association football, or soccer, is the world’s most popular sport. Its biggest stars and best players are known around the world and can earn astronomical sums, with a 2023 report in Forbes showing that the three highest-paid athletes in that year were all exponents of the beautiful game.

Every week millions of fans attend games, whilst hundreds of millions tune in to watch them live on TV (or streaming services).

If, however, you are something of a newbie to this wonderful sport, it can seem like there is a lot to learn. If you’ve got to grips with offside and you understand the basics of the rules but don’t know your wing-back from your full-back, or your inverted winger from your second striker, then this is the article for you. Here we take a closer look at the key positions in football, focussing on three different aspects of that.

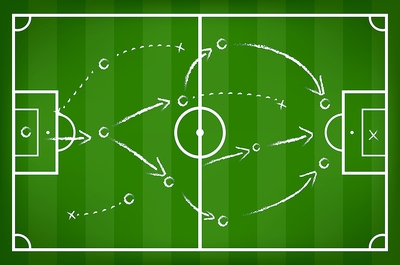

First, we will take a look at the four general “types” of players on the pitch, then we will look at the traditional roles of some of the main shirt numbers, before finally looking in more detail at the very specific positions we encounter in the modern game.

Attack, Midfield, Defence, Goalkeeper

The four broad positions a footballer might play are attack, midfield and defence… and goalkeeper.

We will cover them broadly first before going into more detail on the variations within these positions where they exist.

Goalkeeper

The goalkeeper, of which there can only ever be one on the pitch, is the only member of a team who has a specific and defined role in terms of the laws of the game. This is because they are the only player who can use their hands to touch the ball (not including when players are taking throw-ins, of course).

The goalkeeper, of which there can only ever be one on the pitch, is the only member of a team who has a specific and defined role in terms of the laws of the game. This is because they are the only player who can use their hands to touch the ball (not including when players are taking throw-ins, of course).

Whilst the goalkeeper’s role is generally very different from that of the outfield players, in terms of the laws of the game, that is the only real point of difference. Goalkeepers traditionally take goal kicks and generally stay in their area, the 18-yard box, although this latter point is becoming less fixed in the modern game.

German stopper Manuel Neuer is often held up as the original “sweeper keeper”. This tactical innovation sees goalkeepers often clearing the ball from outside their box (with their feet as hands can only be used inside the area). This allows the defenders to play higher up the pitch, thus squeezing the opposition when they try to play and also offering more support to their own attack.

Pep Guardiola has been central to expanding the goalkeeper’s role yet further. One of his first actions at Man City was to ditch England goalkeeper Joe Hart because he was not good enough with his feet. Pep and many modern coaches want the goalkeeper not just to save the ball but be the first creative player.

In the modern era, the passing range and confidence of keepers on the ball can be astounding and there is no doubt that this position is the one that has changed more than any other over the past 10 years. Many experts believe the goalkeeper’s function within the team will grow yet further, with even more time spent outside of the box.

Defence

In front of the goalkeeper is the defence and this generally consists of three or four players. There is so much flexibility, with different teams and managers using defenders in a range of ways, and these changing frequently and evolving. Fundamentally, however, the main task of a defender is to stop the opposition from scoring.

In front of the goalkeeper is the defence and this generally consists of three or four players. There is so much flexibility, with different teams and managers using defenders in a range of ways, and these changing frequently and evolving. Fundamentally, however, the main task of a defender is to stop the opposition from scoring.

Over the past 40 years or so defenders can be primarily classed as either centre backs or full backs. Centre backs typically play in the middle, with teams tending to use two or three of these. They are generally the most defensive outfield players on the pitch, with average-touch heat maps showing them to be the players whose involvement is closest to their own goal.

That said, in terms of the rules, any player can carry out any function, unlike in a sport such as netball where certain players are restricted to defined areas of the pitch and tasks. As such a centre back can move freely around the pitch and, especially at corners and free kicks, can be found attacking the opposition goal.

Full backs operate to the side of the centre backs, with the left back playing in a defensive roll near the left touchline (as viewed by their own goalkeeper) and the right back on the opposite flank. Once again, their primary role is a defensive one, though increasingly in the modern game they will look to attack as well.

Midfield

Midfielders play, as the name might suggest, in the middle of the pitch, in between defence and attack.

Midfielders play, as the name might suggest, in the middle of the pitch, in between defence and attack.

A midfielder’s role can be very flexible and include responsibilities at both ends of the pitch – the so-called box-to-box midfielder.

Alternatively, they can be more specialised, with most of their work taking place in their own half – a defensive midfielder – or alternatively their opponents’ half – an attacking midfielder.

There are further subdivisions within these jobs but another, broader split in the types of midfielder also exists.

Similar to that which we mentioned in defence, midfield players are sometimes separated into those that operate more on the flanks and those that play more centrally.

Wide players, especially in a 4-4-2 formation, are often expected to help their full backs defend whilst also getting forward to supply width and crosses at the other end of the pitch.

Attack

Attackers, sometimes called forwards or strikers, although this latter descriptor is more of a specific position, especially if prefixed with “out-and-out”, largely operate in what is often called “the final third”.

Attackers, sometimes called forwards or strikers, although this latter descriptor is more of a specific position, especially if prefixed with “out-and-out”, largely operate in what is often called “the final third”.

Playing mainly in their opponent’s half, and indeed often in or close to the box, their chief tasks are to create and score goals.

Once again, however, they have other jobs, and back in the 1980s and 1990s Ian Rush, very much an out-and-out striker, was often referred to as Liverpool’s first line of defence.

In the modern game we talk about the “high press” and this is a similar concept – that the forwards work hard to help their team and potentially try and win the ball back from the opposition in a dangerous area of the pitch.

As with the other main player types, when it comes to attacking footballers, there are a number of different roles.

As well as the main striker, the number nine, of which more below, there is the deep-lying, or second striker, as well as wide forwards.

Position as Defined by Shirt Number

Many fans of the Premier League see nothing unusual about a right back wearing the number 66 shirt (Trent Alexander-Arnold) or a goalkeeper in 32 (Aaron Ramsdale). Shirt-number protocol has changed many times over the years, beginning in 1928 when Arsenal played Sheffield Wednesday wearing numbers 1 to 11, with players assigned a number based on the standard formation of the time, the shocking-to-modern eyes formation of 2-3-5!

Since then different systems have been used in different tournaments and leagues but for a long time there was the idea that each number correlated to a specific position, or at least a general role. This changed, seemingly for good, when the Premier League introduced squad numbers ahead of the 1993/94 season. Initially such numbering was still based on the traditional system and clubs might list what they believed was their first-choice team in shirts 1 to 11. Over time this became less rigid and we gradually saw more unusual shirt numbers being requested, with some famous Premier League examples of the past including Roy Keane in the number 16 shirt and defender William Gallas replacing Denis Bergkamp as Arsenal’s number 10.

Nowadays the links between a player’s number and their task on the pitch are weaker than ever. This is especially true beyond the defence and goalkeeper, though as we have seen with Alexander-Arnold and Ramsdale, these positions are certainly not immune from the use of alternative numbers.

Despite this, we still hear talk of a player being “a traditional number 9”, or that a new signing can operate as “a number 4, an 8 or a 10”. Indeed, Jude Bellingham wore the number 22 at both Birmingham and Dortmund to reflect just that – his ability to play in those three roles.

But what is a traditional number 9, a number 4, a number 8 or a number 10, and what do the various numbers mean?

Number 1

Number 1 is the obvious shirt to start with and also the easiest to explain. This is the traditional goalkeeper’s number, with the chant “England’s number 1” referring more to the fact that they are England’s goalkeeper, so number 1 in the sense of the wearer of that number than being their first choice/best stopper. Note, however, that in the modern game outfield players can also wear the number 1 and, somewhat bizarrely, Dutch legendary midfielder Edgar Davids was Barnet’s number 1 for a while.

Number 9

If a player is described as a number 9, it means they are the most advanced player on the pitch and an out-and-out, or traditional, centre forward or striker. Scoring goals is their main job and there is also, often, an implication that they are a tall, strong player who is good in the air. Everton have had a long line of such number 9s, including more recently Duncan Ferguson, but also Graeme Sharp, Bob Latchford and Joe Royle. Alan Shearer was another archetypal number 9, although Fernando Torres was also a number 9 for Liverpool, both in terms of his shirt and his positioning, despite not being that sort of imposing striker.

Number 10

The number 10 role is often a team’s star man, with Pele, Maradona and, of course, Lionel Messi, all being classic number 10s. They can be viewed as a striker and are certainly highly attacking players, that are expected to score a lot of goals. However, their role is more creative than a number 9 and they are more of a playmaker who operates deeper, often between the lines (in the gap between an opposition team’s midfield and defence).

Number 4

Moving to a more defensive role, if a player is described as a number 4, one can assume they are a defensive midfielder. Centre backs often wear the number 4 which illustrates the limitations of using numbers as positions, and the confusion it can cause. This is partly because formations and tactics have changed over time and also because different footballing nations have different ideas about what a certain number might mean. Indeed, in many ways, the concept of numbers as positions is something of a continental one.

For the most part, we are basing our explanations on current thinking in the UK and, therefore, although many central defenders wear the number 4, if we hear about signing a player “as a 4”, we can assume they are a holding midfielder. Claude Makelele is perhaps one of the most famous number 4s in Premier League history and he was so good in that defensive position that it became known, for a while at least, as “the Makelele role”. Patrick Vieira also played in the 4 shirt for Arsenal, and although adept at the defensive side of things, he was more of a box-to-box midfielder really.

Number 6

Like the number 4, the number 6 is often worn by a centre back but in more modern times the role of a 6 is, again, often that of a defensive midfielder. When Chelsea boss, Thomas Tuchel spoke often about playing with a “double-six”, by which he meant operating with two defensively minded central midfielders. The 6 also has the notion of being a pivot, operating between their defence and the more attacking members of the midfield.

Number 8

A number 8 is an attacking midfielder who may also operate as something of a box-to-box player but with more emphasis on the attacking side of things than the defensive. They play centrally and, whilst expected to score and create goals, are far more of a midfielder than a number 10. Both Frank Lampard and Steven Gerrard wore the number 8 for their main clubs and also often fulfilled the role of an 8. Of course, this was the problem with trying to dovetail the duo internationally because a side can only really have one such player.

Specific Football Positions

The positions we talk of have changed and evolved as we have discussed already, and are often linked to the most popular formations of the day. In the 19th century teams might have lined up in a, wait for it, 1-1-8 formation. Such a formation clearly could not have had two central defenders and two full backs.

A 2-3-5 was a popular formation for many years in the 20th century too, with the left back and right back the only two defenders and more akin to central defenders now. This formation included positions, or certainly names for them, that no longer exist today, such as left-half, right-half, inside-left and inside-right.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, English football was dominated by teams playing a 4-4-2 formation. This consisted of two central defenders, flanked by full backs, a left back and right back; two central midfielders, with a left and right winger to their sides; and two strikers. Towards the end of the century, there were some common modifications, with strikers often “split”, meaning one played deeper as a “second striker”.

In addition, some teams might play three centre backs and use wing backs instead of full backs. A wing back is a more attacking version of a full back with more license to get forward due to the fact that there is an extra central defender. This evolution of tactics, formation and positions has continued and now we will look at some of the most modern innovations within the game.

Inverted Wingers

Inverted wingers are players who are operating on the opposite side of the pitch than would be expected.

Traditionally a left-footed player would play on the left wing, allowing them to cross the ball more naturally. However, in recent times such players prefer to start on the right side of the pitch.

This limits their crossing options on the run but does mean they can cut inside and shoot much more readily.

Inverted wingers are used more commonly in either a 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1 formation, as opposed to a 4-4-2. Certainly when we use the phrase we are probably talking about players in such a structure, as opposed to wingers in a 4-4-2 who are on the opposite side to their natural one.

This is partly because players in a 4-4-2 are more focused on crossing and creating, whereas those in a front three, or playing wide behind a loan striker, are expected to score more goals and be more involved in central areas.

Arjen Robben was arguably one of the best inverted wingers of his generation and the next few as well, especially during his time at Bayern Munich.

Inverted Full Backs

Perhaps the most recent innovation is that of the inverted full back, a position, or rather tactic, pioneered by Pep Guardiola. In fact, Johan Cruyff, such an influence on Guardiola, used inverted full backs when at Barca but the role has really become more developed over the past few years. Guardiola first tried it with Philipp Lahm at Bayern, before converting the German into a midfielder.

More recently Joao Cancelo, Oleksandr Zinchenko, John Stones and Trent Alexander-Arnold have been used in the role – but what is it?

Traditionally a full back’s non-defensive role was moving forward up the touchline to support the winger, overlapping and potentially getting crosses into the opponent’s box. However, Guardiola places so much emphasis on overloading in central areas of the pitch and as such, an inverted full back moves into the middle and becomes an extra central midfielder.

This enables a team to control possession more easily and beat the press of the opposition. It also allows a side’s number 8 to play in a more advanced role. Should their team lose the ball they may stay centrally initially before moving back into a more traditional defensive role as play progresses. As such, a 4-1-4-1 without the ball can become a 3-2-4-1 with it.

Overlapping Centre Back

Where a team plays with three centre backs it has not been uncommon to see one, usually the central one, step out of defence and into midfield.

The overlapping centre back sees the defender go much further forward and, also, it is one of the wider of the three who joins the attack – Anel Ahmedhodzic was a good example of an overlapping centre back when he played for Sheffield United.

An overlapping centre back will advance beyond and outside their wing back.

This can create an overload in the wide areas and commits an extra man into the attack.

It also allows the wing back to play a little more centrally and thus get an extra player into the box, whilst offering an element of surprise as well.

The same players can also perform as underlapping centre backs, coming inside their wing back and themselves getting involved in play inside the opposition box.

False 9

The false 9 is another modern position and one that Guardiola has had a big say in developing.

As with many supposedly new and innovative football tactics and positions, there are those that say it is simply a new name for something that has long existed. Spain were perhaps the first team to play with a false 9, although other experts date its use to the 1890s.

No matter when it was first employed, when a team plays with a false 9 they do not generally field a recognised out-and-out striker in the shape of a number 9 as detailed above.

Instead, a false 9 will tend to drop deep, playing closer to the role of a 10 or even dropping back further to an 8 in midfield.

The person playing in this role is often, in fact, a midfielder by ‘trade’ and they seek to create and exploit space, allowing for a greater interchange of positions that sees unexpected players given more time and room in the box.

Lionel Messi is one of the greatest players the world has ever known, and he played as a false 9 – and he did an awful lot of scoring in that position too.